Note: This article covers the origins of the trope, how it erroneously became associated with silent films and why the myth persists. For more details on the actors involved, the Snidely Whiplash connection and examples of this trope subverted, check out my follow up article.

Cut to the chase: This is a myth. The cliche actually had its start in Victorian theater. It was neither common nor expected in silent films.

“Oh yeah, silent movies. Those are the ones where the villain in a top hat ties a woman to the tracks, right?”

Those words are sure to get a silent movie fan just a little irritated. (Okay, a lot irritated.) You see, we know that silent movies are rich artistically and have an array of subject matter that is truly impressive. Yet the railroad tracks keep being brought up and the people asking are always curiously specific. The villain must wear a top hat and a mustache as he carries out his crime.

Know this: In all my years of watching silent films (and I have seen hundreds in every imaginable genre) I have never once seen this cliche in the wild, so to speak. Not once. It’s so rare that when I challenged a large group of silent film buffs to name one occurrence in a serious, mainstream silent feature, no one could do it. Think about that. Thousands of silent films viewed between us and no one could name a single feature.

I’m still waiting…

Plus, even if one or two occurrences were to surface, there are still thousands of silent movies that do no such thing. So the cliche can hardly be called “iconic” which is how some critics have described it.

But I am getting ahead of myself. First thing’s first. How did this misconception get started? Was the cliche ever actually used?

(I am making the foolish assumption that you are reading this in the spirit of movie scholarship, film trivia or simple curiosity. If this is just a “thing” that you’re into, this article won’t help. Shoo.)

Origins

The start of this trope is generally traced back to Augustin Daly’s 1867 play Under the Gaslight. It can be read online here. Here is the pertinent passage, vintage stage direction intact. And please note, for those who notice these things, it is not a damsel but a gentleman in distress.

And yes, the imperiled gentleman’s name is Snorkey. I can’t help thinking that it sounds like a Muppet character…

Snorkey You ain’t a going to shoot me ?

Byke No !

Snorkey Well, I’m obliged to you for that.

Byke {Leading him to platform.) Just sit down a minute will you.

Snorkey What for. (Laura appears horror struck at window. )

Byke You’ll see.

Snorkey Well, I don’t mind if I do take a seat. (Sits down. Byke coils the rope round, his legs.) Hollo ! what’s this ?

Byke You’ll see. (Picks the helpless Snorkey up.)

Snorkey Byke what are you going to do !

Byke Put you to bed. (Lays him across the R. R. track.)

Snorkey Byke, you don’t mean to — My God, you are a villain !

Byke {Fastening him to rails.) I’m going to put you to bed. You won’t toss much. In less than ten minutes you’ll be sound asleep. There, how do you like it ? You’ll get down to the Branch before me, will you ? You dog me and play the eavesdropper, eh I Now do it if you can. When you hear the thunder under your head and see the lights dancing in your eyes, and feel the iron wheels a foot from your neck, remember Byke! (Exit l. h. e.)

Laura, who has been locked in the station, breaks down the door with an ax and pulls Snorkey from the tracks in the Ta-Da! nick of time.

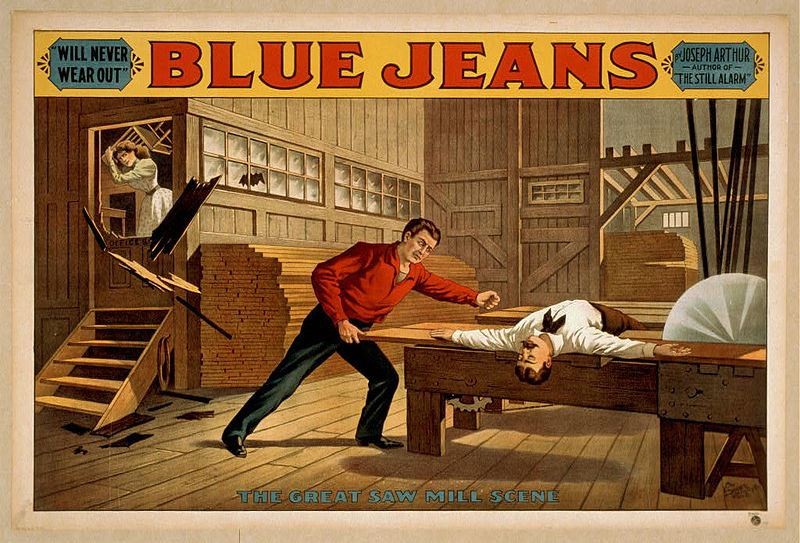

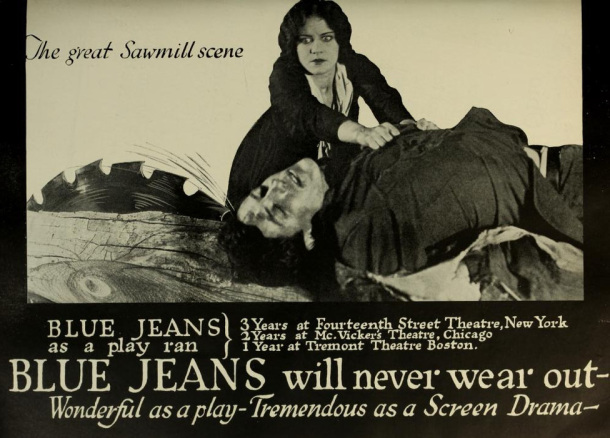

The play was a huge hit and soon people were being tied to tracks left and right. Not just tracks either. The popular 1890 play Blue Jeans by Joseph Arthur featured the hero being knocked out and placed on a moving conveyor belt with a buzz saw at the end. It is worth noting that, once again, the heroine of the play breaks down a door and saves the distressed fellow just in time.

The popularity of this trope is understandable. It was an easy way of creating suspense on the stage and it could be cheaply done. The audience did not have to see the train, they just had to hear the whistle to feel suspense. As you can also see, this plot device was not aimed solely at women.

This is where silent movies come into it…

Silent movies of the so-called nickelodeon era (for the purpose of this article, we will say that it is 1905-1915) were a mixture of original material and adaptations of popular novels and plays. Then, as now, filmmakers knew that a recognizable title would provide box office insurance. It was only natural that early silent movies would either adapt or imitate popular classic plays like Gaslight or Blue Jeans. (Both plays, I must repeat, featured men in distress who were rescued by women.)

What movies feature this cliche? Very, very few, as a matter of fact. A commonly cited film is Edwin S. Porter’s 1905 melodrama The Train Wreckers. Nope. As stated before, the “tied to the train tracks” thing has some weird rules attached to it. Mustache and top hat are a must and the victim must be tied. In this case, the heroine is knocked out cold and simply left on the tracks. No soap.

I have heard some people mention The Perils of Pauline as an example of this cliche. I have not seen it used in the extant footage or available printed material. I think perhaps there is some confusion between the original serial and the dreadful 1947 film of the same name starring Betty Hutton.

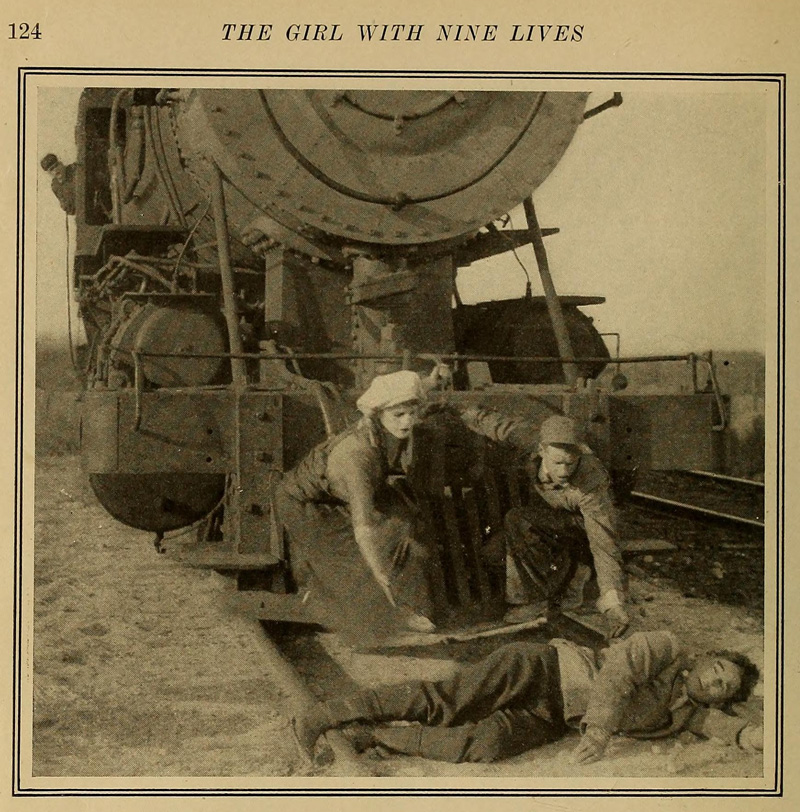

Trains were the most common form of mass transit for most of the silent era and they did often figure into movie plots, both for comedy and drama. However, silent film danger was coed and MEN WERE ENDANGERED TOO.

I repeat my challenge: Anyone who can find a single example of this cliche in a silent feature film from a major studio, come forward please and collect your prize. I have never had any takers.

I’m sorry to disappoint everyone but it there just are not that many uses of this cliche in silent films.

Well, except…

No one can take a joke…

(Above: An amateur film from 1924. Because we all know that home videos are the same as studio releases.)

People who have never seen a silent movie seem to have trouble recognizing the difference between a spoof and a serious film. At this point, I am going to introduce Mack Sennett and his merry band of anarchic comedians, who enjoyed skewering pop culture of the period. Name a movie that was released and it is a sure bet that the Sennett gang would have a send-up ready to go in the blink of an eye.

Again, it was only natural the Sennett would take aim at the popular classic stage plays and the films that they inspired. And so, Sennett leading ladies like Mabel Normand and, later, Gloria Swanson each took a turn being tied to the tracks.

These films are funny. The problem is that people sometimes only see the “chained to the tracks” clip and assume that it is being played straight! Writers confidently assert that Barney Oldfield’s Race for Life was the start all of that tying-to-tracks business. It may have started a trend of poking fun at the trope but that is a totally different thing.

By the time Teddy at the Throttle rolled around in 1917, filmmaking had grown more sophisticated and confident. Oh, stage plays were still revered and old melodramas were still being filmed. It’s just that filmmakers of this period were better able to create suspense without relying on the old stage tricks.

(I should also note that in the 1917 film, Gloria Swanson saves herself!)

To bring things back to the misuse of these clips, it seems that this is a trap that snares all too many would-be silent film commentators: Need serious silent movie footage of a woman tied to the tracks. None available. Fine, use a comedy, it’s the same thing right?

No, it is not. It’s like taking, say, Madagascar (2005) spoofing Saturday Night Fever and using it as proof that disco was the hottest trend of the early 2000s. That would be ridiculous and you would be called out on it.

Come on, nobody really believes this!

Yes, I’m afraid they do. And they don’t understand the nuances of silent film or the differences between comedies and serials and straight dramatic features. To prove my point, I did a quick search in Google Books for references to silent films and women tied to tracks. Here’s a small sample of off-hand, wrong-headed references in books on assorted topics. These took me just a few minutes to gather, imagine how many I would have found it I actually sunk some time into this.

Also, duct tape was invented in 1942 and thanks for referencing “tinny” piano. You win Silent Movie Know-Nothing Bingo.

Darn it, we have Know-Nothing competition! That’s an interesting movie you never saw, sir or madam.

Sigh. I weep for our authors and their sloppy research.

So, where does that leave us on the whole Railroad Tracks question? My solution is to look at them innocently and ask “What was the title of that one again?”

Let me just make this clear: While aspects of the “mustachioed villain ties heroine to tracks” cliche made their way into five or six silent titles (and the silent era lasted for decades), it simply did not exist in mainstream silent films for the most part.

There were plenty of suspense tropes that were much more common. The home invasion robbery, for example, was a popular suspense film plot. But it is the woman tied to the tracks that people remember.

Why?

I think it is a combination of two factors:

First, silent comedies are generally considered to be more accessible than silent dramas. And the enduring popularity of Mack Sennett films assured that the cliche would be viewed by many people.

Second, later movies and television shows portraying early silent films and stage melodramas made use of the cliche. It became an easy shorthand for “old-fashioned villainy” and no one bothered to check how common it really was. Remember, classic Hollywood films about the silent era were quite often contemptuous.

As a result, silent film fans are constantly on call to debunk one of the most persistent myths about the art.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.